Corky: the Survivor

By Christina Colvin

No other whale has endured captivity for as long as Corky. For 48 of her 52 years of life, Corky has been bred, displayed and required to perform for human amusement.

Corky was born in the chilly Pacific waters of British Columbia. When she was four years old, she saw seven of the whales in her family being captured and taken away to be sold to the entertainment industry. A year later, she, too, was separated from her mother when a giant crane attached to a sling hoisted her out of the sea and onto a truck.

Her first stop was at Marineland of the Pacific in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, where she was reunited with three other whales from her pod, Kenny, Patches and Orky. Within three years, Kenny and Patches died at Marineland. Orky and Corky were alone.

Corky has been pregnant a total of seven times, and of her babies born alive, none would live for more than two months. In an attempt to assist her new-born Spooky, born on Halloween in the small, circular tank, Corky had to keep placing her face between the tank wall and her baby to prevent him from hitting the edge of the tank. Because Corky had to block Spooky from the tank wall again and again, he learned to mistake the white patch by her eye, rather than the white patch on her belly, as the right place to nurse. Spooky died within 11 days of being born.

From August 1993: In this Nightline segment, Paul Spong, orca researcher and expert on the Northern Resident pods, debates employees of SeaWorld San Diego and Marineland of the Pacific over whether Corky could have been rehabilitated and reintroduced to the wild at that time.

Corky is often set upon by her tank mates, probably because she’s from the Pacific, and most of the other whales are Icelandic. And while orcas in the wild can live 80 to 90 years, and sometimes even longer, SeaWorld often describes 48-year-old Corky as an “old” whale. She has developed cataracts, is almost blind in one eye, and she has failing kidneys and worn teeth, a premature aging syndrome common to living in concrete tanks for so long.

A kind and patient soul

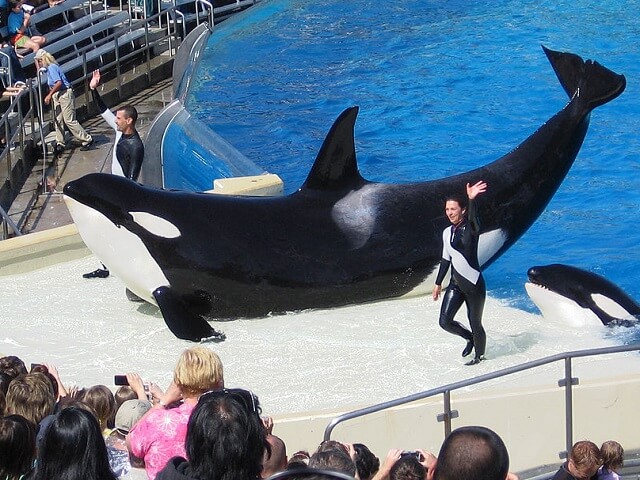

In 1987, Corky was transferred to SeaWorld San Diego. where, since she had fewer incidents of aggression than some of the other whales, she worked frequently with new trainers and became one of the main performers, inheriting the stage-name “Shamu.”

She would intentionally modify her behavior to make sure inexperienced trainers would not be harmed while learning to perform with her.

For those who know her, Corky remains a kind and patient individual. Former trainer John Hargrove says that Corky would intentionally modify her behavior to make sure that inexperienced trainers would not be harmed while learning to perform with her.

For example, rather than taking new trainers to the very bottom of the tank for a “hydro” move – a maneuver in which a whale pushes a trainer through the water and high into the air – Corky would take them just over halfway down. And she would do this, John says, for no other reason than to protect them.

“Corky was the first killer whale I ever got in the water with,” John says. “She’ll always have a special place in my heart.”

For nearly 50 years, Corky has chosen to use her intelligence and caring nature to make choices that help the humans working with her and keep them safe. In response, we must ask: how can we use our intelligence and caring to show our appreciation for what Corky has given us? Can we respond to her caring with compassion of our own?

In 1984, Paul Spong, director of OrcaLab, a research station on Hanson Island in British Columbia, launched the “Free Corky” campaign to return the last surviving Northern Resident captive orca to her family, the “A” pod. At that time, Corky’s mother Stripe (A23) was still alive. Stripe has since passed away, but Corky still has a brother and sister who are alive and flourishing in the ocean.