Following the sad news yesterday about the death of killer whale Kasatka at SeaWorld San Diego, SeaWorld wrote that she had been “part of our orca family.”

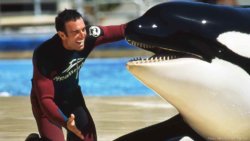

Kasatka in 2001 with former SeaWorld trainer John Hargrove.

But Kasatka was never part of their family. Quite the opposite: she’d been captured and taken from her true family off the coast of Iceland in 1978 when she was about a year old and still just a baby.

During her life, Kasatka was transferred from one aquarium or marine park to another, and then to another, 15 times. Over the years, she was artificially inseminated, including from Tilikum, who, like her, was captured from Icelandic waters at a young age. She gave birth to two daughters and two sons, and she had six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. The youngest of the grandchildren, Kyara, died last month when she was just three months old.

SeaWorld posted a memorial to Kasatka, calling her “The Matriarch.” If she had grown up with her family in the ocean, Kasatka might indeed have become the matriarch of her whole extended family, which, as far as we know, is still swimming the waters of the North Atlantic as a unified pod.

“If you truly love somebody, set them free.”

In the wild, an orca baby is surrounded by her family: her mother, aunts, grandmother and often great-grandmother, who play an active part in raising the calves and who carry the knowledge and culture of the whole social group. Instead, the family to which Kasatka gave birth in captivity is spread across three marine parks, separated by thousands of miles – an unnatural, indeed tragic, matriline.

Kasatka was first diagnosed with pneumonia in 2008, and was being treated for a recurring bacterial respiratory infection ever since. (Her last calf was conceived in 2011, when she was already suffering from this infection.) A recent photo on the Voice of the Orcas website shows a deformed lower jaw and some serious skin problems.

Kasatka’s trainers and caregivers talk and write about how much they loved her. But there’s little evidence that she felt loved or that she reciprocated their feelings. While she generally behaved as required in exchange for food, she sometimes fought back against her captivity, once attacking a trainer, Ken Peters, and dragging him to the bottom of her tank.

Kasatka’s trainers and caregivers talk and write about how much they loved her. But there’s little evidence that she felt loved or that she reciprocated their feelings. While she generally behaved as required in exchange for food, she sometimes fought back against her captivity, once attacking a trainer, Ken Peters, and dragging him to the bottom of her tank.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about that incident, however, is that, rather than drowning him, she let him up for air, took him down again, and then let him go. Apparently, she felt she’d made her point.

The saying goes that “if you truly love somebody, set them free.” So, if the people at SeaWorld truly love the whales in their concrete tanks, now would be a good time to take these words to heart. And while Kasatka’s family have never seen beyond the walls of their concrete tanks and cannot just be set free and released into the ocean, there is certainly a good alternative: retiring them to seaside sanctuaries.

Just as the National Aquarium in Baltimore is planning to retire its dolphins to a warm water seaside sanctuary, marine parks would do well to start the necessary planning for their captive whales to be retired to a cold-water sanctuary of the kind that the Whale Sanctuary Project is creating.

This would make it possible for them to live out their lives in an environment that’s as close as possible to their natural habitat while still receiving the very best of human care.

The whales have given their lives to entertaining people and bringing profits to the marine parks. It’s time to return the favor by giving them back as much as possible of what has been taken from them.