In the wake of two young captive orcas dying so far this year at the Moskvarium Aquarium in Moscow, the facility has admitted that keeping captured whales in concrete tanks is fundamentally unworkable.

On June 23rd, the aquarium announced that Nord, a 16-year-old male orca, who was captured in 2013, had died of an acute peptic ulcer.

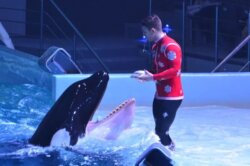

Photo of Nord by Oxana Federova

Only five months earlier, on January 8th, it posted that Narnia, a 17-year-old female orca taken from the ocean several years ago had died of an acute volvulus (the abnormal twisting of a portion of the gastrointestinal tract).

Naya, a 12-year-old female, is now the one remaining orca at the aquarium.

These latest two deaths are part of a worldwide pattern of illness and death that characterizes the lives of captive orcas – whether wild-caught or captive-born – in concrete tanks. In the wild, male orcas live to an average age of 30 (maximum 50-60 years) and females live to an average age of 46 (maximum 80-90). Most captive orcas do not live beyond their early 20s.

Following the passing of Nord, the Moskvarium admitted publicly that it is impossible to close the gap between what orcas need to thrive and what life in a tank is like for them.

It is impossible to close the gap between what orcas need to thrive and what life in a tank is like for them

“Despite the high level of competence of the center’s experts … it is extremely difficult to approximate the artificial conditions for keeping large marine mammals to natural,” it wrote in a statement. The facility has called for a “complete ban on catching marine mammals for educational and cultural purposes.”

The Moskvarium notes that its Center for Oceanography and Marine Biology took part in the development of a law that comes into effect in Russia in September 2024 and provides for a complete ban on “the capture of marine mammals for cultural and educational purposes.”

Photo of Narnia by Moskvarium

The decision to end catching orcas and other marine mammals for entertainment is certainly laudable but it does not ban the breeding of these animals in captivity. Science tells us that captive-born orcas have just as poor, if not poorer, well-being in the tanks as those who were born in the ocean.

The aquarium also notes that in 2019, its experts participated in the rescue and return to the ocean of the 97 orcas and beluga whales who were being held at the infamous “whale jail” near Vladivostok after being captured for sale to entertainment parks in China. (The Whale Sanctuary Project also worked with the Russian government and with Russian animal protection groups. See our posts on Whale Aid Russia.)

The question now is what will happen to Naya, the remaining orca at the Moskvarium who is being kept under conditions that, for a highly social and intelligent mammal, are inhumane. The stress of being the sole individual in a highly artificial environment after experiencing the deaths of two other orcas could lead to her demise, too.

Just as the Miami Seaquarium is now working with the nonprofit Friends of Toki toward transferring its lone orca Tokitae to a sanctuary environment, the Whale Sanctuary Project and our colleagues in the wildlife sanctuary community stand ready to work with the Moskvarium toward determining what are the next best steps for Naya to ensure that she has the highest possible quality of life so that she doesn’t follow the same path as Narnia and Nord.

Title photo of orca Nord by Moskvarium.