(Second in a series on beluga whales in captivity.)

One day in 1861, 11-year-old Sarah Putnam wrote in her diary:

“I went again to the Aquarial Gardens and there we saw the Whale being driven by a girl. She was in a boat and the Whale was fastened to the boat by a pair of rains [sic], and a collar, which was fastened round his neck. The men had to chase him before they could put on the collar.” (the Massachusetts Historical Society)

What Sarah had seen that day was one of the first beluga whales to be captured and put on display in the United States.

Drawing of a performance at the Aquarial Gardens, 1861.

For several years, entrepreneurs and adventurers, including the infamous P.T. Barnum, had been scrambling to be the first to exhibit whales. Sarah had seen this beluga at the Boston Aquarial Gardens, which had opened in 1859. William E. Damon’s 1879 book Ocean Wonders: A Companion for the Seaside describes the same thing:

The first [whale] ever captured for such a purpose was secured by Prof. H. D. Butler, who brought it in perfect health to Boston, Massachusetts, where it was kept in an immense glass reservoir.

… It continued in good condition for more than a year, and became so perfectly acclimated to its new home that it actually showed some signs of intelligence. There was a nautilus shaped boat made, to which he was occasionally tackled and taught to draw. I fancy he was not very fond of being treated like a draught-horse; for when we wanted him to “hold up” to be harnessed, he just put on speed and went all the faster around his glass-walled circle.

He would, however, sometimes condescend to take a live herring or a squirming eel from my hand, and then, turning on one side, sail around and look for more of the same sort; and in other ways he would show that he was really becoming an intelligent Americanized citizen.

If the whale Damon wrote about really survived a year, that would have been a major success for the industry. Some of the belugas didn’t even survive a few hours. This one would probably have lived a few weeks or months, and would have been replaced by another, probably several others, as the year went on.

P.T. Barnum exhibited the first two belugas he’d captured in Boston 1861, and then drove them to the American Museum in New York where they died a day or two later. Barnum didn’t need to worry about the belugas dying; after all, there were thousands more to be found where these had come from in the St. Lawrence Seaway. He wrote:

Even in this brief period, thousands availed themselves of the opportunity of witnessing this rare sight. Since August I have brought two more whales to New-York, at an enormous expense, but both died before I could get them into the Museum.

A fifth living whale has now arrived here, and will remain in the Museum as long as he lives. Perhaps this will be but a few hours, but in order to prolong his life as long as possible, I have, at an expense of $7,000, laid a six-inch cast-iron pipe from the river to the Museum, through Fulton-street and Broadway, and by means of a powerful steam-engine working night and day, the whale is constantly supplied with pure salt water at the rate of three hundred gallons per minute.

This whale (some fifteen feet long) is undoubtedly the greatest “blower” in New York. I leave this monster leviathan to do his own “spouting,” not doubting that the public will embrace the earliest moment (before it is forever too late) to witness the most novel and extraordinary exhibition ever offered them in this City.

Over the next four years, at least nine whales were displayed at the museum. None of them survived long, and in 1865 the two remaining belugas died when the entire museum went up in flames.

More aquariums were now springing up, along with businesses that made their money by keeping belugas in holding areas in Canada so they could be quickly shipped down to the new marine zoos whenever one who was on display died.

In Appleton’s Popular Science Monthly (July 1899), Fred Mather writes about belugas at the Coney Island aquarium that he managed:

The management would keep whales penned up in the St. Lawrence River to replace those which died, and would never show more than two at a time, claiming that they were rare animals and only to be had at an “enormous expense.”

… It would never do to have the public know that they were common in the St. Lawrence in the summer, and when one was getting weak, another would be sent down, and the public supposed the same pair was on exhibition all the time.

Of one of the belugas who had died less than a month after arriving, Mather wrote that he sounded hoarse and had a kind of cough, and that his female companion “slackened her pace day by day to accommodate it to that of her constantly weakening companion, and as the end neared she put her broad traverse tail under his and propelled him along.” As soon as he died, his companion was sent across the Atlantic to the Royal Aquarium in London, where she died four days later.

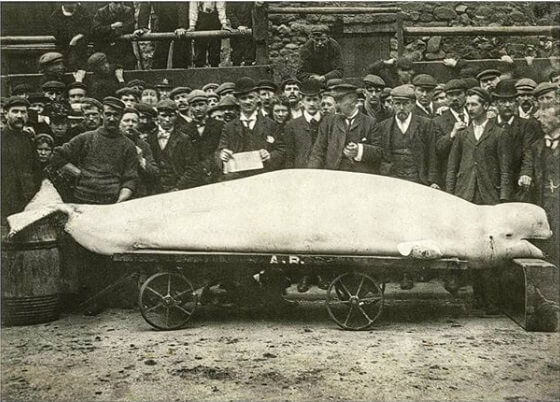

A few years later, in June 1903, a beluga was taken captive off the northeast coast of England was taken captive after who having been caught in the nets of fishermen. The 14-foot whale put up quite a fight, towing two boats four miles out to sea before succumbing to exhaustion. Back on shore, the dead beluga was purchased by two people, who, in turn donated the skeleton to the Hancock museum in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, but not before taking this photo of the dead beluga whale on a large metal-wheeled trolley with his head propped up on an upturned crate and his tail on a barrel.

Photo courtesy of @nee_naturalist, @gnm_hancock.

By this time, however, at the turn of the century, many of the aquariums were closing. Barnum and several of his competitors had died, and the novelty of seeing belugas in a tank was waning. And then came the Great Depression and the war years.

But in the late 1950s, the beluga industry began to pick up again. This time, Alaska became the favored place to capture belugas from their families, and in June 1958 two belugas, Louey and Bertha, were captured off the Alaska coast and put on a plane to New York. They died on the plane about an hour before landing.

But the captivity industry persisted, and a new generation of marine zoos and circuses, including SeaWorld and the Georgia, Shedd and Mystic aquariums in the United States, and Marineland and the Vancouver Aquarium in Canada, found more successful ways to capture belugas, ship them to their display tanks, and keep them alive longer than P.T. Barnum had been able.

Regardless of the industry’s new techniques, however, today’s aquariums and marine parks continue to have serious problems keeping belugas alive and healthy. While a beluga in the wild can expect to live up to 60 years or more, few adults in captivity live beyond the age of 25, and baby belugas born in captivity often don’t survive beyond a few months.

– – – – – – – – –

For more history:

- Barnum’s Whales: The Showman and the Forging of Modern Animal Captivity an article by Amanda Bosworth that adds much fascinating detail to this post

- Captive Belugas: A Historical Record & Inventory, published by CETA Base, an online database of captive marine mammals.

- The Forgotten Aquariums of Boston by Jerry Ryan. Available free here as a pdf.