On July 24th, a team of divers assembled at the sanctuary site in Port Hilford Bay, Nova Scotia, to conduct phase three of the Environmental Site Assessment (ESA III). The ESA series is a key requirement in understanding the health and suitability of the ecosystem for whales who are being retired from marine entertainment parks.

On July 24th, a team of divers assembled at the sanctuary site in Port Hilford Bay, Nova Scotia, to conduct phase three of the Environmental Site Assessment (ESA III). The ESA series is a key requirement in understanding the health and suitability of the ecosystem for whales who are being retired from marine entertainment parks.

History of the ESA Series

The series had begun with an ESA I, which is a general assessment of whether samples of soil and sediment should be taken for analysis. The reason for doing an ESA I was that when we were first considering Nova Scotia as a possible location for the sanctuary, we learned that there had been historical gold mining in several regions of the province from the 1880s to the 1930s and that there might still be remnants of gold mine tailings on the 30 acres of sanctuary lands.

During our two-year site search, we had researched 130 possible locations in British Columbia, Washington State and Nova Scotia. We’d found beautiful locations in British Columbia, but they were all too remote to be practical. And off the coast of Washington State, by contrast, either the human population was just too dense, or the sites were not available. It was therefore clear that the West Coast was not an option for this first whale sanctuary.

In Nova Scotia, however, there was one location that rose to the fore above all others: Port Hilford Bay, Wine Harbour, where we found an excellent site and a welcoming community. And after local consultations, we concluded that any issues related to historic gold mining could be mitigated, just as is the case in many other coastal locations in the province. (For details on how we conducted the search and the basic criteria by which we judged each location, go here.)

One location that rose to the fore above all others, where we found an excellent site and a welcoming community.Our decision to pursue Port Hilford Bay as the best location in North America prompted extensive environmental studies. These included analyses of currents, tidal flows at multiple depths; flushing rates; benthic surveys of flora and fauna; storm tracking and seasonal changes over two years, and many more. (Examples of some of these are described here.)

The last of these environmental studies is the ESA series, which comprises analyses of soils, submerged land and the waters along the shore of the sanctuary site to understand everything that may be necessary to develop the sanctuary site including any remediation work. Based on our understanding that there had been a gold stamping mill in this location, the ESA I led directly to an ESA II sampling and analysis of land-based soil and groundwater.

The ESA II began in the spring of 2022 and our consultants sent us the results six months later in September, noting that areas that contain elements that might be disturbed by construction work can be mitigated by covering them with a layer of soil, gravel or concrete.

Their report also recommended a geotechnical “review of subsurface conditions at the site in relation to the site development plans” and a follow-up study to analyze terrestrial groundwater. The results of this, which we received in May 2023, led to an ESA III study of submerged soils and invertebrates.

The ESA III study

The ESA III study began in July 2023 with a professional dive team collecting 18 core samples from the seabed.

The study team was joined by Wayne T. Joy of Deep Perspective Diving, who volunteered his time to join the team. Wayne’s remarkable photos of the fish, the crabs and all the other animals, grasses, sea plants and diverse life forms demonstrate what a robust and vibrant seascape it will be for whales coming from marine parks.

Summary of the work

A total of 27 sediment samples were collected from several locations across the site, including the on-site pond and surrounding wetland areas. The team collected a total of 21 marine sediment samples, including three coastal/intertidal locations, along with six terrestrial sediment samples.

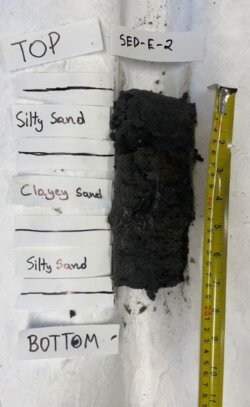

Twelve of the marine sediment samples were collected into Shelby tubes (i.e., cores) that were 25cm long. In the other six cases, where insufficient sediment thickness or if bedrock or other large granular sediment was encountered, the available surface sediments were collected directly into glass sample jars provided by the laboratory. All Shelby tube sediment samples were kept in cool storage prior to submission to the laboratory.

Alexandra Vance, our Nova Scotia Project Manager, supervised the work and explained the work of the dive team in the following Q&A.

Q: This has been a long series of studies. It even took three months after the end of the second ESA II for us to be able to start the ESA III. What was the delay?

A: There are all kinds of unexpected delays in a project for which the governmental agencies have no precedent. In this case, because the ESA III studies would involve taking core samples from the seabed, we needed two separate permits from the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables – one for sediment and water, and another for invertebrates. We applied for the marine sampling (sediment and water) permit back in April 2022, but it expired in December before we got our marine invertebrate permit, so we had to re-apply. We got the permit renewed in June 2023 and brought the dive team to the sanctuary site to execute the sampling in July.

There are all kinds of unexpected delays in a project for which the governmental agencies have no precedent. Q: How long do results generally take for these kinds of tests?

A: Our consulting firm told us that it would likely be six weeks for the laboratory to get back preliminary results and that those would be very crude results, just a large Excel file with lots of numbers. It would take a few more weeks to synthesize those results into a report that we can actually interpret. So, I’d say we’re looking at mid-October at the latest.

Q: What are we expecting to see in the results?

A: We’re probably going to see some level of metals near the shore adjacent to where we know there was the gold stamping mill. So, we would expect that some of these will have washed into the water from rainfall and general run off. And we would expect to see some deposition in the ground water on that shoreline adjacent to the gold stamping mill and in the adjacent submerged soil. Which is why we’re doing these analyses.

Q: What steps will we have to take regarding whatever we find?

A: We already know about the areas that are on land. Government standards require that any areas that are going to be exposed will need to be covered with a layer of soil, gravel or concrete.

You obviously can’t do just that in the ocean. That’s why we want to know whether some of the soil has washed away and if so, how much of it may have washed away.

Q: Talk a little about the core samples that we took.

A: We took samples from the seabed that went about 25 centimeters deep. You can see them in the photo that one of the divers took. It’s a metal tube with two rubber caps: one on top and one on bottom. You take that metal core tube, place it on the seabed at the bottom, and use a rubber mallet to hammer it in. Then you put the top cap on to keep the soil from leaking out when the tube is pulled from soil before the bottom cap is attached to the tube.

The divers had to try different things to use as mallets because using the same one at each place didn’t always work, especially when they got to harder mud. But they definitely got the hang of it by the end.

Q: There’s a lot of gear involved in the diving work. Can you explain some of it?

A: There’s two different kinds of scuba. One is where you bring the air tank on you; the other is where it’s on the surface or in this case, the air tank is on the boat. The orange, the blue and the yellow lines have his air (called the umbilical), his communications, and a rope that‘s tethered to him.

In one of the photos, you can see he’s got two lights, one on either side of his helmet. One of them has a camera on top of that. And inside his helmet is a two-way communication so he can speak freely back to the captain on the boat.

And in another photo, you see the captain talking to him and watching the video in real time. So, the diver would hold something up and be asking is this one of the invertebrates you want to look at? And I’d be right there next to the captain and saying no, not that one … yes, that one. So, we were actually able to identify exactly what we needed in real time without having the diver bring samples to the surface. We wanted to cause as little disturbance as possible, and to be the least invasive we possibly could to these wonderful creatures.

Incidentally, the photographer wasn’t wearing that gear with the umbilical. His diving suit is very self-contained.

Q: So, back to the core samples.

A: At the lab, they’ll be analyzing both the top half and the bottom half of the core samples separately, so we’re not just homogenizing the entire sample. In each case, we’ll be able to see if there’s a difference between surface sediments and bottom sediments.

Q: Did you select the places where the divers took the core samples based on the geography of the sanctuary site and what we already know from our earlier studies of the tidal flows and currents?

Exactly. If you look at a map of those 18 sample sites, they’re all within our proposed boundary of the site and we have a good relatively randomized swath of our whole site.

Q: Is it possible that ESA III is going to lead to an ESA Four?

A: No. This is the final stage of the ESA series we’ve needed to do – both to meet the governmental requirements in Nova Scotia and to satisfy our own need to be sure that the site is suited to the care of whales. We’ve done lots of other environmental studies, too, and some of them have involved several years of testing – like water temperatures and flows through all seasons over a period of years. There may well be more work to do, but completing the ESA series certainly represents a major milestone.

Also: Take a virtual tour of the sanctuary site – or four of them by boat, by air and by land.