Ellen Cuylaerts travels the world as a freelance underwater and wildlife photographer, documenting animals in each region and the challenges they face. We talked with her about her visits to Hudson Bay to photograph beluga whales in their home waters.

“Belugas swimming past me, not bothered by my presence, just cruising.”

You don’t often see really good photos of beluga whales in the wild. In fact, you don’t often see any photos of belugas in the wild. That’s because, while most other whales roam far and wide in the ocean, belugas make their homes in the arctic and sub-arctic regions and don’t venture south very much.

But award-winning wildlife photographer Ellen Cuylaerts has a passion for belugas, and the photos she has captured on her expeditions to Hudson Bay are unlike any others. She says it began when she was growing up in Belgium and went to a dolphinarium.

But award-winning wildlife photographer Ellen Cuylaerts has a passion for belugas, and the photos she has captured on her expeditions to Hudson Bay are unlike any others. She says it began when she was growing up in Belgium and went to a dolphinarium.

“Of course, as a kid it’s amazing to see such animals closely. But I could also feel the hurt and the suffering, and since then, I’ve always felt strongly about marine mammals of all kinds in captivity. These creatures are intelligent, they live in complicated family structures, and they roam the oceans in freedom.”

Ellen migrated from Europe to the Caribbean in 2009 and soon began diving. “I wanted to capture the soul of my subjects and tell the story about their nature and habitat,” she explains. “I dived and snorkeled with sharks after learning how to behave with them in the water, and how to read them.”

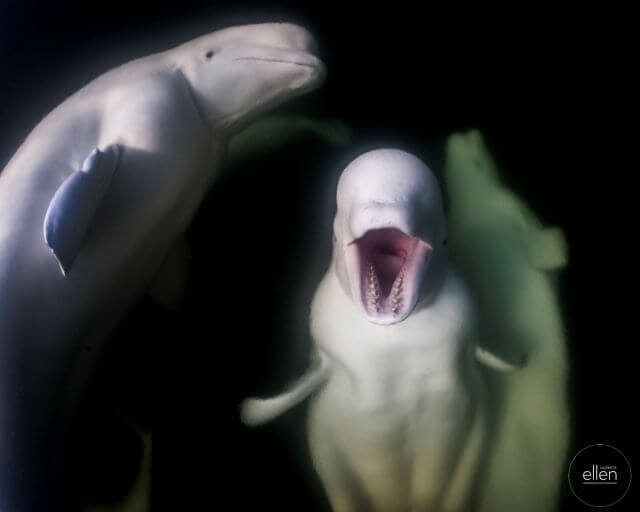

“Beluga whales lack a very pronounced rostrum or beak like most dolphin species have. Instead they have a flat snout. And instead of a dorsal fin, they have a tough dorsal ridge that preserves body heat (less surface area to lose heat) and allows them to swim easily under ice floes. Its a characteristic of all Arctic whales.”

And then, one day, she was approached by a solitary dolphin. “I realized that being in the water with very intelligent and complex creatures was more difficult, and you need to be even more switched on to react correctly. They feel your vibes and they’re very picky about any interaction.”

Ellen spent time with spinner and bottlenose dolphins in Hawaii and with sperm whales in Dominica. And then her fascination with whales and dolphins took her to Canada to photograph belugas.

“I was determined to show the belugas

in their world”“I’d learned about how they migrate to Hudson Bay during the summer to feed and to give birth to their young. But I’d also seen images of them that had been taken under the ice, and I’d learned that those animals were kept in a closed sea pen and that some wildlife photographers were not concerned about ethics and didn’t care about their subjects. Taking an image of an animal in captivity is not showing them in their natural habitat. I was determined to show the belugas in their world, so I decided to go to Churchill further north, and by myself, even though going alone can be quite challenging when you’re traveling with photo gear and drysuit and there are lots of logistics.”

The first year Ellen visited Churchill, the weather conditions were not the best and the visibility underwater was no more than one foot. “I could hear the belugas with all their vocalizations, but I hardly saw them at all!”

A year later, however, she was back in Churchill and the water was a bit clearer.

“Once I caught the interest of the belugas, they swam closer to me and checked me out, circling sometimes and nodding. Unlike in other dolphin and whales, the neck vertebrae of belugas are not fused, which allows them to move their head from side to side and nod.”

Beluga whales are known for their curiosity and intelligence, their playfulness, and their spirited personalities. But Ellen says that as a photographer, you need to keep them interested. If they’re not engaging with you, they will just swim past, nod their head a few times, and move on.

“So, I tried to move in the water like they did, twisting and turning, nodding my head and being vocal. Mothers with calves made several swim-by’s, and females without calves would turn around and sometimes come straight up to me to check their reflection in my dome. The males were mostly bolder, and one day I had two pods of males come up to me. They started bumping each other and me, and it felt like they were trying to impress me with dominance behavior, so I got out of the water. Still, they stayed next to the boat for the next half hour and were very loud!”

“Two pods of male belugas displayed some dominance behavior by snapping at each other while being extremely vocal. The image is a bit blurry in the background due to two layers of water with a different temperature coming together and causing a thermocline.”

Swimming with belugas is now restricted in Churchill, and Ellen has mixed emotions about that. She hopes the whale watching tours will continue in a way that’s respectful toward the animals. And she adds that her interactions with them in the ocean have only added to her conviction that whales and dolphins simply do not belong in captivity.

“They suffer when they’re held in small concrete tanks and sea pens where they’re out of their normal social network,” she says. And she sees no merit in any of the claims that keeping them captive has education and conservation value.

“We should observe them responsibly in the wild to learn more about their natural needs in order to better protect their habitats while we can.”

(You can find out more about Ellen Cuylaerts and her work on her website and on her Instagram page.)