The governor of Russia’s Primorsky Region has affirmed that the 10 orcas and 87 beluga whales being held captive at the “whale jail” in Srednyaya Bay will be returned to the ocean.

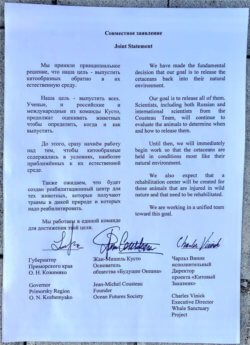

On Monday, Governor Oleg Kozhemyako sat down in Vladivostok with Charles Vinick of the Whale Sanctuary Project and Jean-Michel Cousteau of Ocean Futures Society to sign a formal agreement. The text reads:

Photo by Harry Rabin.

“We have made the fundamental decision that our goal is to release the cetaceans back into their natural environment.

“Our goal is to release all of them. Scientists, including both Russian and international scientists from the Cousteau Team, will continue to evaluate the animals to determine when and how to release them.

“Until then, we will immediately begin work so that the cetaceans are held in conditions most like their natural environment.

“We also expect that a rehabilitation center will be created for those animals that are injured in wild nature and that need to be rehabilitated.”

“We are working in a unified team toward this goal.”

From left: Charles Vinick, Oleg Kozhemyako, Jean-Michel Cousteau at press conference in Vladivostok. (Photo by Harry Rabin.)

This agreement is the essential first step that opens the door to the various parties collectively working out the details for each of the individual orcas and beluga whales who are being held captive.

“A decision in principle has been taken to release all the animals into the wild,” the Governor told reporters.

The rehabilitation and release of these whales will take time. At an earlier press conference in Moscow at the Ministry of Natural Resources, Vinick and Cousteau emphasized that each of the animals will need individual treatment and that readapting some of the whales to their natural environment might take years.

“Each of the animals is an individual and has to be treated as an individual,” Vinick explained. “The challenge for rehabilitation and release is complex. And therefore, we need to work together to identify a strategy for rehabilitation and for reintroduction or release of as many of those animals, one by one, as is possible.”

Dr. Lori Marino, President of the Whale Sanctuary Project, explains each of that each of the whales has had to cope with the trauma of capture and confinement in their own individual way.

“They are just like us that way,” she says. “So, each and every one of them has to be evaluated individually to determine his or her mental and physical health and what they need.”

Some of the whales are so young, they were not even weaned when they were captured, and they may have never even had the experience of catching food on their own. Instead, during their time in captivity, they have been hand-fed dead fish.

“So, instead of having been brought up as part of a family that works together to catch food,” Dr. Marino says, “they will have to be taught by us to catch live fish on their own. And because they are kids, they still have a lot of learning ahead of them. We will have to act as substitute mothers and aunts and older siblings and teach the young whales what they would have normally been learning from their families.”

In order to accomplish this, Governor Kozhemyako announced that a special rehabilitation facility would be set up under the agreement, with conditions as close as possible to the whales’ natural environment.

Jean-Michel Cousteau (right) with Gov. Oleg Kozhemyako and Charles Vinick at one of the beluga sea pens at the “whale jail.”

After the signing ceremony, the team traveled to Srednyaya Bay, about 200 miles north of Vladivostok, to begin their initial assessment of the whales. After spending time at the sea pens, Cousteau commented that this is very much an international effort.

“The people taking care of these animals and members of our team who are representing many parts of our planet are working together,” he said, “to come up with solutions to see what we can do with the whales to release them [at once] or to take them into rehabilitation.”

Cousteau described the signing of the agreement as a very emotional moment for him. Much work lies ahead, he said. “But I have no doubt that we are going to succeed.”