It was a landmark study in our understanding of the cognitive abilities of dolphins. But it was also the last study on captive whales and dolphins that I would be involved in.

The year was 2001, and I was working with another scientist, Diana Reiss, at the New York Aquarium to see if bottlenose dolphins could recognize themselves in a mirror. The ability to recognize that the face in the mirror is “me” has long been considered a key measure of self-awareness.

When we use a mirror to put on make-up or brush our hair, we are demonstrating that we have a sense of self. Twenty years ago, only great apes and human children age two and older were known to understand that the reflection they see in a mirror is themselves.

But when, at the New York Aquarium, my colleague and I placed a large mirror in one of the tanks, the two captive dolphins there, Presley and Tab, were fascinated by what they saw. And they made it quite clear that they understood that the dolphin each of them looking at was himself.

Presley examines himself in the mirror.

We spent over a year employing tightly controlled experimental methods and analyses to ensure that Presley and Tab were indeed doing what they looked like they were doing. And they were.

(For details about how the study worked, read our peer-reviewed paper.)

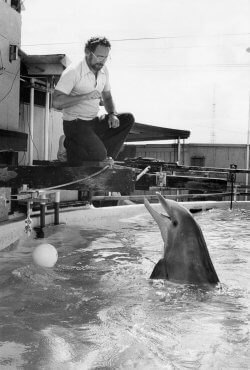

Researcher Lou Herman at the Kewalo Basin lab. Photo by Walter Sullivan.

Once our paper was published, Presley and Tab shot to international fame as the first cetaceans to demonstrate the ability to recognize themselves in a mirror. And they and our study garnered attention from the international media, late-night talk show hosts and cartoonists at major newspapers.

But now I was beginning to see the two dolphins as much more than just research subjects. Presley and Tab were self-aware individuals who had large, complex brains. And they were living in a tiny barren tank in Coney Island, New York. And while the starkness of the tank had been a benefit to our ability to control all of the conditions of the mirror experiment – there were no distractions – it was now revealing to me the dismal existence of these dolphins, endlessly swimming in circles within run-down concrete walls.

And then, not long after the study, these two profoundly intelligent and sensitive beings would meet untimely deaths from diseases related to stress and immune-system dysfunction. Presley succumbed to fungal encephalitis at age 19, Tab to gastroenteritis at 21. Both diseases are related to stress and immune-system dysfunction.

What I learned most from the study was that dolphins and whales do not belong in concrete tanks.I now understood the real significance of our mirror study: Presley and Tab were not just research subjects; they were victims. I felt ashamed that their “reward” for what they had shown us was just more exploitation, suffering, and the loss of their lives.

I soon learned about other cetacean “research superstars” who had died in the tanks. They included all of the dolphins in the famed experiments by Louis Herman at the Kewalo Basin lab in Hawaii. Phoenix, Akeakamai, Hiapo and Elele had died prematurely: two from cancer, one from enteritis and toxemia, and one from unknown causes. None of them lived past the age of 27.

Natua, another bottlenose dolphin at the Dolphin Research Center in Florida, had provided definitive evidence that dolphins reflect upon what is on their minds (called metacognition). He died at age 18 of hepatitis and cirrhosis.

And NOC, the beluga whale who mimicked human speech, had died of aspergillus encephalitis at the young age of 24 at a U.S. Navy facility in California.

Dolphins captured from blood-stained waters in Taiji, Japan. Photo by Oceanic Preservation Society.

I also learned about the monstrous Taiji drives and the role of the marine park industry in supporting the slaughter of up to thousands of cetaceans every year. And for me to continue doing research in a marine park or aquarium setting would amount to a tacit endorsement of the abuse. I could not live with that.

Instead, I would use my scientific training to protect and advocate for these psychologically complex beings. This led to participating in the films Blackfish and Long Gone Wild as the tide of public opinion began to move in the direction of bringing an end to treating whales and dolphins as a product for entertainment.

But it was also clear that without an alternative to these facilities, there would be no path to ending the confinement of cetaceans in marine parks. And all of this has led to the work of the Whale Sanctuary Project to retire captive whales and dolphins to sanctuaries.

Today, the need for sanctuaries is greater than ever. This year alone has seen numerous more deaths and reports of abuse and neglect in captive whales at home and abroad. And as the reports pile up, one after another, the need for sanctuaries grows ever more urgent.

The sanctuary we are creating in Nova Scotia is designed to be the first of many – a model that can be replicated all over the world. I believe that this is the least we can do as an act of reparation toward these intelligent and emotional beings. Together we can give them back as much as possible of what has been taken from them by our own species.