What began as a global outcry has now evolved into a work of international cooperation. And it came into high relief in Moscow as people of many nationalities gathered at the Ministry of Natural Resources to begin a long-term effort to return 97 illegally-captured orcas and beluga whales to the ocean.

A team of experts, brought together by Jean-Michel Cousteau of Ocean Futures Society and Charles Vinick of the Whale Sanctuary Project had been invited to meet with government officials and Russian scientists. And at the end of the meeting, Cousteau and Vinick sat down with the Minister of Natural Resources Dmitry Kobylkin for a press conference.

It would not be overstating what transpired to say that the day was a classic example of what happens when people of different backgrounds and cultures come together to cooperate on a greater mission: doing good for our fellow animals.

One of the highlights was when, in a gesture of friendship, Minister Kobylkin presented Cousteau with the remarkable gift of a stunningly beautiful ammonite fossil.

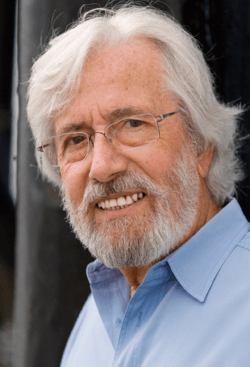

Jean-Michel Cousteau of Ocean Futures Society

Cousteau told reporters that this mission is “the most exciting time of my life,” emphasizing that “we are not here to criticize; we are here to work together and find solutions.”

To which, Kobylkin replied that “We are being led by our science and by the vision that we have to run this work as openly as we can. We especially value the international experience.”

None of this is to say that what lies ahead will be easy. Vinick explained some of the challenges that the team will face.

“Each of the animals is an individual and has to be treated as an individual,” he said. “The challenge for rehabilitation and release is complex. And therefore, we need to work together to identify a strategy for rehabilitation and for reintroduction or release of as many of those animals, one by one, as is possible.”

Charles Vinick of the Whale Sanctuary Project

Cousteau and Vinick both emphasized that this will be a long-term project that will likely take several years before all the orcas and belugas are rehabilitated.

And that will mean long-term cooperation among the many people involved. It also means that we all go into this with our eyes fully open as to not only the complexities of the work, but also the potential for differences and conflicts of opinion and personality. That’s human nature. But when we rise above these inevitable disparities and keep our focus on the animals who depend on us, then the outcome can be one that fulfills the vision that was laid out at yesterday’s gathering in Moscow.

After the press conference, the team departed Moscow for a nine-hour flight to Vladivostok, and then on to Srednyaya Bay, where they will visit the whales.

Here is some background to the mission to return the whales to the ocean

Last November, reports started to emerge that more than 100 orcas and beluga whales had been captured and were being held in small, crowded pens in Srednyaya Bay on Russia’s far east coast. Russian animal protection groups were calling it a “whale jail,” a term that quickly caught on in the national media.

A month later, animal advocate Anastasia Kovalenko launched a petition on Change.org that quickly drew hundreds of thousands of signatures, mostly Russian. When actor and environmentalist Leonardo DiCaprio promoted it on his personal and Foundation social media pages, more signatures poured in from around the world. (Right now, the petition has close to 1.5 million signatures.)

Meanwhile, winter had set in and temperatures had begun to plummet in Russia. During the long nights it had become a challenge for the whale captors simply to keep the sea pens free of surface ice so the whales could breathe. The situation was becoming an emergency.

President Putin steps in

Late in December, President Putin directed the new Governor of the Primorsky Region, Oleg Kozhemyako, to address the problem.

In January, a group of Russian scientists and government officials visited the whale jail, where they collected skin and breath samples and water samples from the pens. The video footage they took showed skin lesions on and around their dorsal fins, suggesting frostbite or a fungal or bacterial infection, or both, and a skin infection that was likely the result of rotting food being left in the pens.

A few weeks later, one of the orcas was no longer to be seen in any of the sea pens. The captors claimed that he/she had escaped, an explanation that was generally considered absurd.

Letters to President Putin prompts an invitation to Moscow

A few weeks later, four prominent whale experts, including Cousteau and Vinick, wrote to President Putin, offering to visit the whales and then advise the government on what could be done to return them to the ocean. Thirty-four marine mammal biologists also sent a letter to Putin, as did a group of global citizens including Queen Noor of Jordan, Dr. Jane Goodall, Sir Richard Branson, actor Pamela Anderson, along with other business leaders, actors and musicians.

Skin lesions, frostbite, and a fungal or bacterial infection or both.In response, Governor Kozhemyako of the Primorsky Region invited Cousteau to visit the whale jail” and Cousteau and Vinick began to gather a team of experts that would travel to Srednyaya Bay to assess the situation and advise the government.

At the beginning of April, the Whale Sanctuary Project received a formal invitation to meet with Minister of Natural Resources and Environment Dmitri Kobylkin and with Russian scientists and then to travel to Vladivostok and visit the whales at Srednyaya Bay.

At the end of this visit, the team will compile a report to submit to the Minister of Natural Resources, offering our best advice on a rehabilitation program for the whales with a view to their being returned to the ocean. We will also offer whatever help the government may ask for in the work that lies ahead.

7 Comments

OPEN, THE. GATES. PERIOD.

Why does it take years? Why? Can someone give us an answer?

Lynn, here’s what Dr. Lori Marino posted on Facebook yesterday in answer to a similar question:

Can’t We Just Open the Gates?

Lori Marino, President, Whale Sanctuary Project.

– – – – –

We’re all anxious to see the 97 orcas and beluga whales freed from the “whale jail” in Russia and back in the ocean. And many people have been asking: “Why can’t you just open the gates when the Russian government gives the OK? Why wait?”

So, I’d like to visit some of your questions and discuss the complexities of this issue.

– – – – –

*Can we just open the gates and let them all swim off together in a group all at once?

Well, first of all, they’re not “a group.” Each of the 87 belugas and 10 orcas is an individual and each of them has coped with the trauma of capture and confinement in a unique and individual way. They are just like us that way. So, each and every one of them must be evaluated individually to determine his or her mental and physical health and what they need.

Also, these whales will need to be taught to catch live fish on their own (they’ve been fed dead fish for nine months) and each whale will learn at his or her own pace. So we cannot make a blanket decision for the entire group. Instead, we will need to give careful attention to each and every individual before planning a reintroduction effort.

– – – – –

* Don’t animals have survival instincts?

We tend to think other animals have “survival instincts” that tell them exactly what to do and when and where to do them. But this view of complex beings like whales is not supported by science. Whales, especially belugas and orcas, are highly cultural beings like us – meaning that, like us, they depend on learning their group’s traditions in order to get along in the world. These cultural traditions shape how their basic impulses develop and are used, and without this learning these urges remain formless.

– – – – –

Just like all animals, we humans have an “instinct” to eat and drink, but we will not be very good at obtaining those resources if we don’t learn how to get them.

Also, like the whales, we have self-preservation “instincts,” but we need to learn to identify the dangers we will encounter if we are to avoid them.

These captive whales are young – in some cases very young – and they may not have ever had the experience of feeding on their own. They would have naturally learned to do that from the adults in their social group. And because they are kids, they still have a lot of learning ahead of them. So now humans have to act as substitute mothers and aunts and older siblings and teach the young whales what they would have normally been learning from their families.

We can no more send them out into the open ocean to fend for themselves without rehabilitation than we would drop off a bunch of orphaned human children in a forest and expect them to survive.

Whales and dolphins have big brains and are very intelligent. Can’t they figure out how to survive?

While whales and dolphins are highly intelligent, so are primates, elephants and many other animals. But those other animals are never just rescued and then plunked back into African or Asian forests to eke out their existence. The consequences would be dire. (In fact, when a captive chimpanzee who had grown up in a human home was “returned” to Africa some years ago, the result was tragic.)

Now, these 97 whales in Russia have only been in captivity for a relatively short time – a few months – so their chances for rehabilitation and successful reintroduction are higher than average. But, just like other extremely intelligent animals, we cannot assume that they have the know-how to survive out in the wild just by their wits. And why would we take that considerable risk?

– – – – –

Let’s set them up for success!

Belugas and orcas need to learn how to survive and they need to be with their social groups. The rehabilitation process our team and the Russians will develop will ensure that we do our best to set these young whales up for success. We will get them as healthy and robust as possible, help them learn or re-learn how to catch fish, and, where possible, find their families and social groups. And all along the way, we will be evaluating each one as an individual.

I have to agree with Andi. I cannot see why it should take years at all. There are countless examples of marine mammals fostering babies and juveniles that are not their own. Additionally if the process takes years it will imprint more of a human reliance on them.

I agree! Sometimes one must act first, and leave the talking to … well, those that need to.

“Cousteau and Vinick both emphasized that this will be a long-term project that will likely take several years before all the orcas and belugas are rehabilitated.” Why YEARS?!!!

Thank you for asking. Jean-Michel and Charles explain some of this during the last 10 minutes or so of the press conference. One of the main reasons is that many of the whales are youngsters who were captured from their mothers. In the wild, as is similar with human children, they would learn from their mothers how to catch their own food and how to be part of a family and social group, all working together. But instead of that, they were orphaned. And it will be up to their caregivers to teach them how to live in the ocean. That’s something that can’t be taught overnight.