Shouka: Lonely World Traveler

By Christina Colvin

Shouka’s life has been full of instability and loneliness. She has known the frustration of being socially out-of-place; she has also known the maddening frustration and boredom of total isolation.

Born into captivity in 1993 at Marineland of Antibes in France, Shouka’s first years were spent alongside her mother, Sharkane. (Just four years earlier, whale catchers had snatched Sharkane from open waters off the coast of Iceland.) Unlike many captive-born orcas, Shouka spent nine years with her mother.

Shouka’s life at Marineland was far from idyllic. As a baby, she was drastically underfed. She was the first calf born at Marineland, and the staff had no experience feeding a baby orca. Shouka did not receive the nutrition and sustenance she needed to develop properly, and her physical development was stunted. When she was eight years old, she was so small that she appeared to be only about four and a half.

Acts of aggression

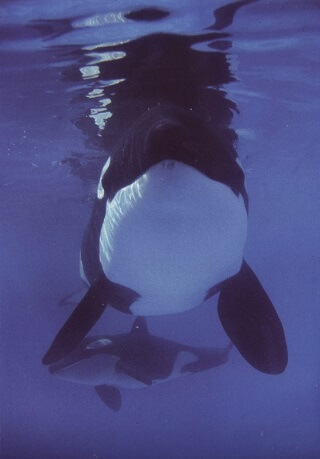

Shouka as a calf with her mother, Sharkane, at Marineland Antibes.

Nor could Shouka find a suitable place in the tiny social hierarchy of the Marineland orcas. From an early age, Shouka was frustrated, which led to her tendency to act out. In one instance, she hit a female trainer so hard that she was rushed to the emergency room with internal bleeding.

Former orca trainer John Hargrove recalls several occasions in which Shouka acted aggressively toward him.

In one case, Hargrove gave Shouka the signal to swim beneath him so he could ride astride her back. Instead of following orders, however, Shouka drove into Hargrove’s back, forcing him underwater and hard against the acrylic wall of the tank.

All of this took place in front of a live audience.

During another performance, Shouka rolled Hargrove off her back and into the water. She retreated, leaving the exposed trainer in the middle of the pool; then she turned around and swam at him, mouth open. During both incidents, Hargrove was able to get Shouka to recognize and respond to one of his signals. It’s as if she changed her mind about the aggression she was planning.

Then she turned around and swam at him, mouth open.

And in yet another incident, Hargrove remembers how Shouka “came up and grabbed my wetsuit at my chest with the very tip of her jaw … and she attempted to pull me into the pool.” Hargrove was only saved by his quick reflexes and the skin-tight fit of his wetsuit. As Shouka tried to pull him into the water, he pulled his weight down and behind him, and his suit popped out of her mouth. Hargrove attests that if she’d managed to pull him into the pool with all seven whales, one of whom the trainers did not swim with, “it’s unlikely I would have survived.”

These aggressive incidents betray the frustrations Shouka must have experienced (and continues to experience) in captivity.

From Antibes to Ohio to California

Shouka is shipped out of Marineland and off to Ohio.

After years at Marineland, Shouka was shipped to SeaWorld’s now-defunct Ohio facility. There, she learned what it meant to be alone. As a gregarious species, orcas live their whole lives in close-knit family groups called pods. In Ohio, Shouka lived completely alone. It cannot be overstated how traumatic such solitary confinement must have been for her.

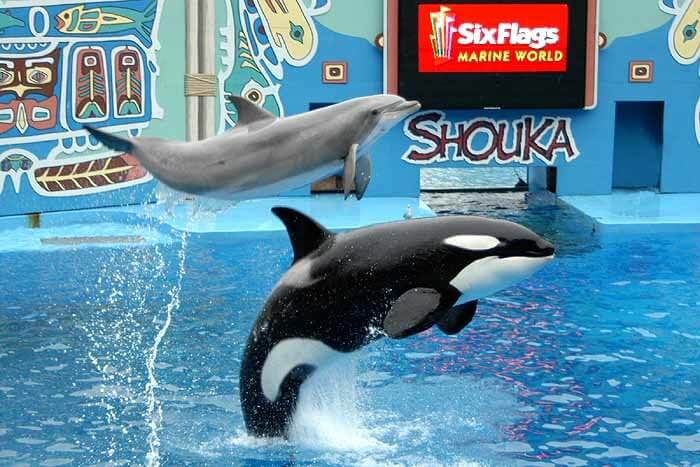

She fared no better after officials moved her to California for display at Six Flags Discovery Kingdom in 2004. Even after being shipped between continents and then across America, she was once again left in isolation. No friend, no family member swam by her side. At the beginning of her tenure at Six Flags, Shouka lived without company for another whole year.

Eventually, Six Flags brought in Merlin, a male bottlenose dolphin, to serve as a companion for her. However, in a violation of the Animal Welfare Act, Six Flags did not even provide Shouka and Merlin sufficient shade. Animal protection groups also reported that although the orca and dolphin were reportedly housed “together,” Merlin and Shouka were routinely separated – another violation or the Animal Welfare Act, which stipulates that these highly social mammals be allowed to live in groups.

A 2008 inspection by the Animal and Plants Health Inspection Service supported these claims. It found that Shouka was indeed held in isolation, reporting that she was “single housed.” Then, in 2011, Shouka’s living situation got even worse when Six Flags ceased all contact between Merlin and Shouka, citing “compatibility issues.”

In total, Shouka endured complete and partial isolation for ten years of her life.

More aggression and frustration

With all the traumatic moves and prolonged periods of loneliness she’s endured, it’s no wonder that Shouka would sometimes take out her frustrations on her trainers. In 2012, she lunged toward one of them, and even after the trainer was knocked backward, Shouka continued her pursuit, lunging forward out of the water two more times.

At Six Flags Discovery Kingdom, California, Shouka with her sole companion, the dolphin Merlin.

Scientist Naomi Rose commented on Shouka’s behavior, saying: “It may be that being entirely solitary is in fact affecting her mood and she is now acting out of frustration over this untenable social situation.”

SeaWorld San Diego took custody over Shouka shortly after the incident in 2012, and she resides at SeaWorld to this day. After ten years without any orca companionship, Shouka can now be seen spending time with Corky, an orca who has lived in captivity longer than any other whale currently alive.

Today, almost all Shouka’s teeth betray severe damage. Out of boredom and frustration, she has a history of biting off pieces of concrete from her pool. Hargrove reports that the bacterial smell coming from her wrecked teeth was overwhelming.

From the time of her birth to the present day, Shouka has endured mishandling, neglect and loneliness. She deserves to experience companionship in a seaside sanctuary, a place where she and her fellow orcas no longer have to fear the pain of isolation.