Tilikum: The Whale Who Rebelled

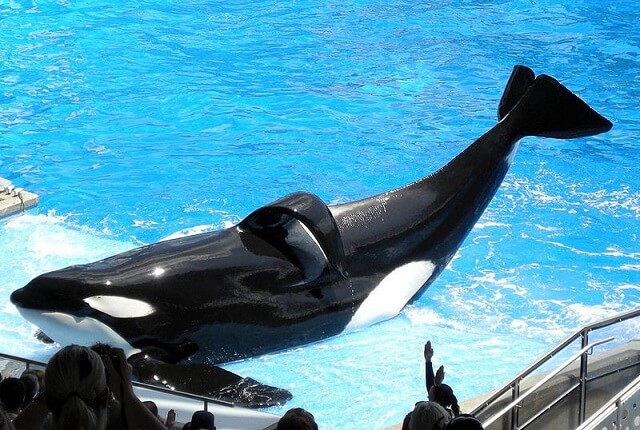

On February 24th 2010, tourists enjoying a “Dine with Shamu” evening behind a giant glass window at SeaWorld Orlando found themselves witnesses to a spectacle they never imagined. As his expert 40-year-old trainer Dawn Brancheau leaned over the edge of his tank during what is called a “relationship session,” the 11-ton star orca Tilikum took her in his mouth, dragged her into the pool, shook her, fractured much of her body, drowned her, savaged her, and killed her. During the attack, he reportedly scalped her and bit off her arm. And even when SeaWorld staff members had trapped and netted him, Tilikum would not let go of the body.

While the captivity industry tried to spin this horrific story as an accident and a playful scene that slipped out of control, audience members said they had little doubt that Tilikum knew exactly what he was doing.

Tilikum age three at the Hafnarfjördur Marine Zoo in Iceland before he was shipped to Sealand of the Pacific.

This was the third time that Tilikum had struck back since his 1983 capture as a two-year-old calf. In February 1991, at Sealand of the Pacific in Victoria BC, when a young part-time trainer slipped and fell into their pool, Tilikum and his two tankmates submerged her and dragged her around the pool. When she managed to reach the side and tried to climb out, they pulled her back down. Staff members threw her a life-ring, but the whales kept her away from it. She surfaced three times before drowning, and it was several hours before her body could be recovered from the pool.

Sealand never recovered from the incident. It closed a year later, and Tilikum was sent to SeaWorld Orlando.

One morning, seven years later, a 27-year-old man was found dead, draped over Tilikum’s back in his nighttime pool. An autopsy found numerous wounds, contusions and abrasions covering his body, and his genitals had been bitten off. Exactly what had happened was never established after SeaWorld claimed that the event was not captured on any of the cameras that monitor the whales.

And then, in 2010, came the death and mutilation of SeaWorld’s star trainer by their star captive orca. This terrible incident became the subject of a book, Death at SeaWorld, and of the documentary film Blackfish, which has led more and more people to question the ethics of keeping these apex predators in concrete tanks.

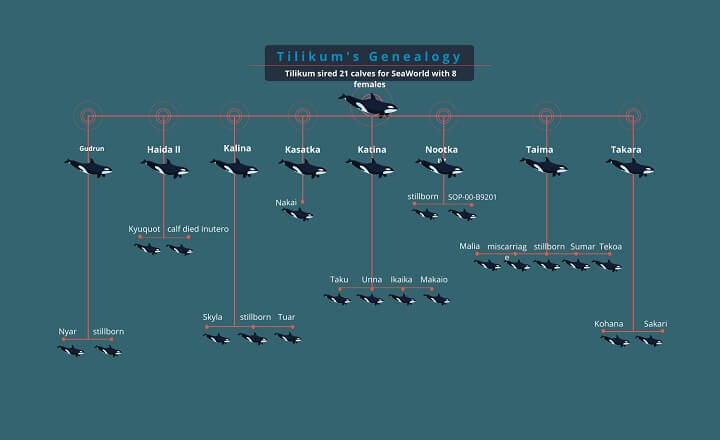

SeaWorld’s audience numbers and fortunes never fully recovered. Tilikum had not only been SeaWorld’s star attraction; he had also been the company’s star breeder, having fathered 18 calves with eight of the company’s female orcas. But under pressure from humane groups, the company in 2016 announced that it would stop breeding orcas. And trainers are no longer allowed in the water with their captives.

Were Tilikum’s actions deliberate?

Meanwhile, in the aftermath of his attack upon Brancheau and his increasing isolation, Tilikum grew increasingly listless, spending most of his time floating in a small enclosure, ravaged by infections, until he died in 2017 from what SeaWorld described as “a persistent and complicated bacterial lung infection,” adding that he had been being treated with “combinations of anti-inflammatories, anti-bacterials, anti-nausea medications, hydration therapy and aerosolized antimicrobial therapy.”

“Their actions have had intent and purpose. If anything, these animals are psychologically strong, not weak. They are choosing to fight back.”While he remains the most famous of SeaWorld’s whales, Tilikum is not the only captive orca to have caused grievous injury or even death to a trainer. Only a few months before Tilikum killed his trainer, Keto, an orca who had been transferred from SeaWorld Orlando to Loro Parque Zoo in the Canary Islands, turned on his trainer and killed him. That incident is explored in Outside magazine by journalist Tim Zimmerman who also writes about the death of Brancheau here. Zimmerman notes that “A frustrated killer whale – whether it’s struggling with captivity, social structure, sexual tension, poor health, or training failures – is a potentially dangerous killer whale.”

Other experts have suggested that whales in captivity suffer from a form of post-traumatic stress, which may certainly be the case. But there is another factor to be considered, one that is perhaps more disturbing: the issue of deliberation. As Jason Hribal concludes in his book Fear of the Animal Planet – the History of Animal Resistance:

“Resistance is not a psychological disorder. Indeed, it is often a moment of distinct clarity. This is not to say that Tilikum and others are not suffering from clinical depression or stress-related ailments. Rather the point is that captive animals have used their intelligence, ingenuity, and tenacity to overcome the situations and obstacles put before them. Their actions have had intent and purpose. If anything, these animals are psychologically strong, not weak. They are choosing to fight back.

“. . . The industry encourages you to think that these animals are intelligent, but not intelligent enough to have the ability to resist. The industry encourages you to care about them, so that you and your children will return for a visit. But it does not want you to care so much that you might develop empathy and begin to question whether these animals actually want to be there.

“. . . We can recognize this struggle, learn from it, and choose a side. Where [did] Tilikum want to be? Certainly not confined in the lonely and sterile tanks of Sea World.”

They are not your family

Zoos and entertainment parks like to claim that the animals are beloved members of the staff’s “family.” But these animals are not part of any human family; they have their own families in the wild from whom they were cruelly taken, or, if born in captivity, their own mothers and siblings from whom they are forcibly separated according to the needs of their captors. When those family bonds are torn apart, the psychological damage is inestimable.

By any definition and by any standard, keeping these apex predators of the ocean in small tanks for the amusement of tourists is more than just wrong; it is a crime against each of them individually and a sin against nature that cannot be righted by the occasional claim of conservation or educational benefit.

In the ocean, whales and dolphins often go out of their way to extend a display of friendship toward humans. But, given the opportunity, a captive whale or dolphin will make it abundantly clear that he or she has no desire to be the prisoner of humans. And if there is any education to be garnered from the miserable lives that Tilikum and his kind have endured, it is surely that the time has come to end the shows and retire the remaining living whales to sanctuaries.