In each region where the Whale Sanctuary Project is conducting our site search, we’ve been helped, guided and encouraged by the First Nations people who have lived in these regions for thousands of years and have a cultural and spiritual connection to the ocean.

Among the First Nations people with whom we have met are the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, the Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis of the Johnstone Strait of British Columbia, and the Lummi of Washington State. This series of posts is a brief introduction to who they are as we have come to know them.

The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia

The Membertou Convention Center

Twenty years ago, The Mi’kmaq nation was suffering from 95 percent unemployment and near-bankruptcy. Unwilling to watch their people slide into ruin, a new team of leaders agreed to abandon the status quo that had been set in place a century earlier by the Canadian government, and to create a different future for their people.

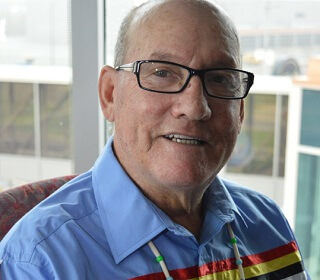

Senator Daniel Christmas

Since that time, Daniel Christmas, Chief Terrence Paul and their brethren have transformed their nation into an economic powerhouse with an operating budget of around $112 million. It is now one of the most successful, thriving nations in the whole country and a model for others that are still struggling under the Indian Act of 1876.

The tribe has built a convention center, hotel, bingo hall, sports and wellness complex, and other work and leisure-related activities, welcoming non-Mi’kmaq into the community and driving what’s often referred to as an economic miracle.

But Christmas’s prescription was practical and straightforward: to throw off the Indian Act, by which agencies and bureaucrats controlled almost every aspect of life on reservations, and for the people to take control of their own destiny. The nearly 150-year-old act purported to support the people, but Christmas called it “a horrible and unproductive existence whose ultimate destiny is insolvency and ruin, both economically and emotionally.”

Chief Terry Paul of the Membertou (Mi’kmaq) First Nation

The Mi’kmaq’s new model for change forged economic progress, but anchored it in the nation’s cultural values, overhauling its education system and building a new elementary school that teaches Mi’kmaq culture and language.

When we visited Chief Paul for the first time in 2017 to consult with him about our mission to create a seaside sanctuary for captive whales, he told us that what we are doing is compatible with Mi’kmaq values and that we would be welcome to seek a partnership with them as we go forward.

After all, the Mi’kmaq have a relationship with whales that goes back thousands of years and is embedded in their mythology and culture. Author Anne-Christine Homborg writes that in the nation’s traditional culture “all beings are depicted as persons.”

That is why ‘Indians’ could ‘speak’ with nature, have animals as spiritual guardians, or even ‘marry’ animals. What the Romantics, popular writers and movie makers who created stereotypical images of Indians do not see is that the tales simultaneously stress an important difference between humans, [other] animals and spirits: a difference in their bodies.

Corporeal diversity thus separates them from each other: It gives them different possibilities: to move, communicate and survive. A whale person has to live as a whale because it has the body of a whale, and a human person has to live as a human because he or she has a human body: but both entities experience their own species as persons.

(Mi’kMaq Landscapes: From Animism to Sacred Ecology – by Anne-Christine Homborg)

In 2016, Daniel Christmas was appointed to the Senate of Canada. (As in the U.K., members of the upper house in Canada are largely appointed in recognition of their contribution to society.) He became a strong supporter of Senate Bill S-203, which would ban any further captive breeding, import, export or live capture of whales, dolphins and porpoises.

The bill, originally sponsored by Senator Wilfred P. Moore of Nova Scotia, is still working its way through the Senate, despite a series of obstacles from a handful of senators, some of whom are tied to the marine entertainment park industry.

“The business of capturing whales for display is shameful.”

Senator Murray Sinclair With Sen. Moore’s retirement, Sen. Murray Sinclair of Manitoba has taken up sponsorship of the bill. The former judge (and the first aboriginal judge to be appointed in his province) is renowned for having chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that held hundreds of hearings to reveal how First Nations children had been taken from their parents and shipped to boarding schools to be educated in British values, religion and culture.

While the Truth and Reconciliation Commission focused on the abduction of children, First Nations people also look to a time of truth and reconciliation with their fellow animals – those other “persons” who, like the Mi’kmaq children, have also been abducted and treated with total disrespect.

NEXT: The Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis: Reconciliation with our fellow animals and the natural world.