This is the text of a guest opinion essay on November 18th in The Globe and Mail, Canada’s leading newspaper

By Lori Marino

One afternoon in 1861, 11-year-old Sally Putnam wrote of an incident she witnessed in Boston in her diary:

“I went again to the Aquarial Gardens and there we saw the whale being driven by a girl. She was in a boat and the whale was fastened to the boat by a pair of rains [sic], and a collar, which was fastened ‘round his neck. The men had to chase him before they could put on the collar.”

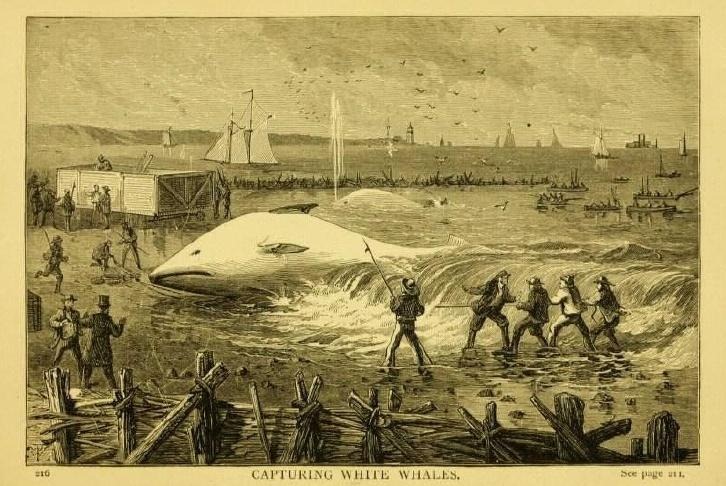

What Sally had witnessed that day was one of the first beluga whales to be captured and put on display in the United States by entertainer and businessman Phineas T. Barnum. The whales came from the St. Lawrence Seaway in Canada, and while most of them did not survive more than a few days, this didn’t bother Barnum. Whales were so plentiful that he only needed to keep a good enough supply penned up in the river to be able to load more onto a train bound to Boston or New York as needed.

Beluga whales have large, complex brains and sophisticated communication capabilities. In the ocean, they live in strongly bonded social groups of mothers, offspring, relatives and friends. In summer they can congregate by the thousands to socialize, mate, give birth, nurse their calves and educate them, including passing down migration routes and communication skills from each generation to the next.

Barnum’s beluga business didn’t last long. In July, 1865, a fire at his American Museum in New York brought the entire five-story exhibit hall of curiosities and animals, including two newly arrived whales, crashing to the ground. Henry Bergh, founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), called out Barnum for his treatment of his captive creatures. And by the turn of the century, many aquariums were closing.

Henry Bergh, founder of the ASPCA, called out Barnum for his treatment of his captive creatures. And by the turn of the century, many aquariums were closing.

In the late 1950s and 60s, however, the captive dolphin and whale industry began to revive. A new generation of marine zoos and circuses, including SeaWorld, Marineland Canada and the Vancouver Aquarium, found ways to capture whales and dolphins and keep them on display. Today, around the world, close to 3,600 cetaceans are being held captive, mostly in concrete tanks, for entertainment. Whatever the incremental improvements in their welfare, the question remains: Can it ever be possible for captive whales and dolphins to thrive in concrete pools?

In a new peer-reviewed paper in the journal PeerJ, six animal welfare scientists and experts, including myself, bring together what we know from all the available peer-reviewed literature to reach three conclusions.

First, the amount of space in any concrete pool is woefully inadequate to provide for the physical and mental needs of wild animals that, in the ocean, can travel hundreds of kilometres every day. Second, the environment at any theme park or aquarium is impoverished and highly predictable, leading to extreme boredom and chronic stress. And third, orcas and other captive cetaceans exhibit stereotypies, swimming in circles and banging their heads and bodies on the sides of the pools, along with other activities that indicate distress, like chewing on concrete surfaces. They also suffer from opportunistic infections and short lifespans.

The best captive facilities provide good food, veterinary care and clean water. And owners point out that the animals don’t have to suffer from predators, pollution, ship strikes and fishing nets. But while the modern captivity industry has had enough time to demonstrate that they can provide a significantly better environment for these megafauna than PT Barnum’s attempts, they have still failed.

Increasingly, public opinion is calling for an end to this outdated form of entertainment, and governments are responding. In 2019, Canada banned the capture, breeding and public display of these animals. Marineland Canada has closed its doors and is looking to sell its property. But in accordance with the law, the government has denied Marineland permits to export the whales to a theme park in China that has one of the most dismal animal-welfare records.

For decades, zoos and circuses have been working with sanctuaries to give a better life to captive elephants, great apes, big cats and other land animals. The time has come for animal-protection organizations, marine parks, aquariums and governments to work together to retire whales and dolphins to sanctuaries and other more enriching environments where they can truly thrive.

Lori Marino is the president and founder of the Whale Sanctuary Project. She teaches about captive wild animal welfare at New York University.